English Gothic Architecture has been broadly divided into periods for the purpose of classifying the styles, the following being the most generally accepted.

_ _ _ _ _

Еxcerpt from the book: A Manual of HISTORIC ORNAMENT TREATING UPON THE EVOLUTION, TRADITION AND DEVELOPMENT OF ARCHITECTURE AND OTHER APPLIED ARTS. PREPARED FOR THE USE OF STUDENTS AND CRAFTSMEN.

BY RICHARD GLAZIER, Associate of the Royal Institute of British Architects; Head Master of the Municipal School of Art, Manchester, LONDON: 1899

_ _ _ _ _ _

Most of our magnificent cathedrals were founded A.D. 1066-1170 by Norman bishops, some upon the old Saxon foundations, such as Canterbury and York, or near the original Saxon buildings as at Winchester, or upon new sites such as Norwich and Peterborough, and were without exception more magnificent erections than those of the anterior period, portions of the older style still existing in many cathedrals, showing the fusion of Roman and Byzantine architecture with the more personal and vigorous art of the Celtic, Saxon, and Scandinavian peoples.

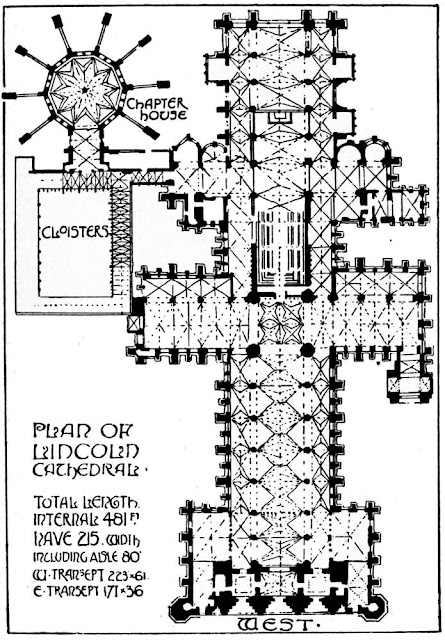

The plan, given on next page, of Lincoln Cathedral shows no trace of the apsidial arrangement so universal in Norman and French cathedrals, and is therefore considered a typical English cathedral.

Each vertical division in the nave, the choir, and transept is termed a bay. On plate 14 is an illustration of four typical bays of English cathedrals, showing the development of style from the 12th to the 15th century.

THE TRIFORIUM & CLEARSTORY. Plate 14.

The general characteristic of each bay is given separately, but obviously it can only be approximate, as the building of each cathedral was influenced by local considerations, each period necessarily overlapping its predecessor, thus forming a transitional style. For instance, in the choir of Ripon Cathedral, the aisle and clerestory have semi-circular Norman windows and the nave arcading has pointed arches. In the Triforium and Clerestory arcading, round arches are seen side by side with the pointed arch.

The Piers (sometimes termed columns) of these bays have{37} distinctive features which are characteristic of each period of the Gothic development. Sketch plans are here given showing the changes that took place in the shape of the pier from 1066 to 1500. The same general characteristics are observed in the arch mouldings and string courses.

CHARACTERISTICS OF THE NORMAN PERIOD.

Nave Arcading.

The universal use of the round arch, cylindrical or rectangular piers with semi-circular shafts attached to each face. Capitals cubical and cushion shaped. Arch mouldings enriched with concentric rows of Chevron and Billet ornament.

Triforium.

In early work, of one arch. In later work, two or four small arches carried on single shafts under one large semi-circular arch.

Clearstory.

One window with an open arcading in front, of three arches, the centre one larger and often stilted. This arcade forms a narrow gallery in the thickness of the Clearstory wall. The roof of the nave, of wood, flat and panelled, roof of the aisles, semi-circular quadra partite vaulting.

An arcading of semi-circular arches was usually placed upon the wall, under the aisle windows.

Early windows are narrow, flush with the external wall, and deeply splayed on{38} the inside. Later windows are recessed externally, with jamb shafts and capitals supporting an enriched moulded arch. A few semi-circular rose windows still remain, of which a fine example is to be found in Barfrestone Church, Kent.

EARLY ENGLISH OR LANCET PERIOD.

The Lancet or pointed arch universal.

Capitals, of three lobed foliage and circular abacus. The pier arch mouldings, alternate rounds and hollows deeply cut and enriched with the characteristic dog’s tooth ornament. A hood moulding which terminates in bosses of foliage or sculptured heads invariably surrounds the arch mouldings. This moulded hood when used externally is termed a “Dripstone,” and when used horizontally over a square headed window a “Label.”

The Triforium has a single or double arch, which covers the smaller or subordinate arches, the spandrels being enriched with a sunk or pierced trefoil or quatrefoil. The Triforium piers are solid, having delicate shafts attached to them, carrying arch mouldings of three orders, and enriched with the Dog’s tooth ornament or trefoil foliage.

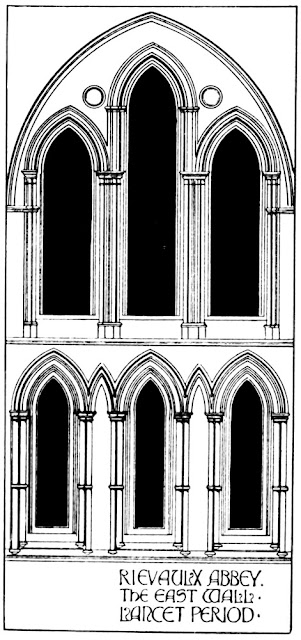

The Clearstory lancet windows are in triplets, with an arcading on the inner face of the wall. The vaulting shaft occasionally springs from the floor, but more usually from a corbel above the nave capitals, and finishes under the clearstory string with an enriched capital, from which springs the simple vaulting usually quadrapartite or hexapartite in form. Early windows in small churches were arranged in couplets and at the east end, usually in triplets, with grisaille stained glass similar to the example given on the next page from Salisbury Cathedral. The annexed example from the east end of Rievaulx Abbey shows a finely proportioned window and its arrangement.

Figure sculpture, beautiful and refined in treatment, was frequently used upon external walls. The figures of Saints and Bishops were placed singly under triangular pediments and cusped arches, of which there are fine examples at Wells, Lichfield, Exeter, and Salisbury (fig. 5, plate 14). Splendid examples of circular rose windows are to be seen in the north and south transepts of Lincoln Cathedral, also at York, but they are comparatively rare in England, while France possesses over 100 of the finest and most important examples of this type of ecclesiastical adornment. They are to be seen in the Cathedrals of Notre Dame, Rouen, Chartres, and Rheims.

DECORATED OR GEOMETRIC PERIOD.

In this, the piers have engaged shafts with capitals having plain mouldings or enriched with finely carved foliage of the oak, maple, or mallow. The pier arches have mouldings of three orders, also enriched, usually with the characteristic ball flower, or foliage similar to that upon the capitals.

The Triforium consists of double arches, with subordinate cusped arches, adorned with Geometric tracery.

The inner arcading of the Clearstory is absent, the one large window being divided by mullions and geometrical tracery, or by equilateral triangles enriched with circular and bar tracery (fig. 3, plate 14). Above the pier capitals an enriched corbel is usually placed from which springs the vaulting shafts, terminating with a richly carved capital under the Clearstory string.

The aisle arcading, as a rule, is very beautiful, having geometric tracery and finely proportioned mouldings, the aisle windows with mullions and bold geometric tracery. The circular rose windows of the transepts are typical of this period.

PERPENDICULAR AND TUDOR.

The Piers of this style are lofty and enriched with shallow mouldings carried round the pier arch, where capitals are introduced, they frequently resemble a band round the pier at the springing of the arch, or occasionally they are octagonal in form, and decorated with an angular treatment of the vine. In some instances, the upper part of the plain octagonal capital is relieved with an embattlement. The latter is also frequently used as a cresting for the elaborate perpendicular screens, or for relieving the clearstory strings.

The Triforium is absent in this period, the bay consisting of two horizontal divisions only. The Clearstory, owing to the suppression of the Triforium becomes of more importance. The windows are large and often in pairs, with vertical mullions extending to the arch mouldings of the window head. The aisle windows are similar, and when lofty have horizontal transoms, on which the battlement ornament is displayed. The aisle arcading being also suppressed, all plain wall space was covered with perpendicular surface tracery. Enrichment of this type was used in the greatest profusion upon walls, parapets, buttresses, and arches, also upon the jambs and soffits of doorways. This, together with the use of the four-centred arch, forms the characteristic features of the Perpendicular or Tudor period.

English cathedrals show a marked contrast in scale to contemporary French buildings. The English nave and choir is less in height and width but greater in length than French cathedrals. For instance, Westminster is the highest of our English cathedrals, with its nave and choir 103 ft. from floor to roof, 30 ft. wide, and 505 feet in length. York is next with 101 ft. from floor to roof, 45 ft. wide, and 486 ft. in length. Salisbury is 84 ft. from floor to roof, 32 ft. wide, and 450 ft. in length, and Canterbury 80 ft. from floor to roof, 39 ft. wide, and 514 ft. in length. Lincoln with 82 ft. and Peterborough with 81 ft. are the only other examples reaching 80 ft. in height; York with 45 ft. being the only one reaching above 40 ft. in width of nave.

The measurements of contemporary French cathedrals on the other hand, being as follows:—Chartres, 106 ft. from floor to roof, 46 ft. wide, and 415 ft. in length; Notre Dame, 112 ft. from floor to roof, 46 ft. wide, and 410 ft. in length; Rheims, 123 ft. from floor to roof, 41 ft. wide, and 485 ft. in length, while that at Beauvais reaches the great height of 153 ft. in the nave, 45 ft. in width, and only 263 ft. in length.

The remarkable growth of the Gothic style during the 13th and 14th centuries was contemporary in England, France, Flanders, Germany, and in a less degree in Italy. One of the most beautiful churches in Italy, is, S. Maria della Spina, at Pisa, with its rich crocketed spires and canopies, features which were repeated a little later at the tomb of the famous Scaligers at Verona. At Venice, the Gothic is differentiated by the use of the ogee arch with cusps and pierced quatrefoils. It was in France and England where Gothic architecture reached its culmination; the abbeys and cathedrals, with pinnacles, spires, and towers, enriched with the most vigorous and beautiful sculpture; the arcadings and canopies with crockets, finials, and cusps, vibrating with interest and details, and the splendid windows filled with glorious coloured glass, are all tributes to the religious zeal and splendid craftsmanship of the middle ages.

On the opposite page are illustrations showing the modifications that took place in the evolution of church architecture from the 12th to the 15th century. The triforium in the Norman period was fundamental, but in the Perpendicular period this feature was absent. The change of style may also be observed in the windows of each bay, from the simple Norman one (fig. 1) to the vertical mullioned 15th century window, figs. 4 and 8.

NORMAN DETAILS

EARLY GOTHIC DETAILS

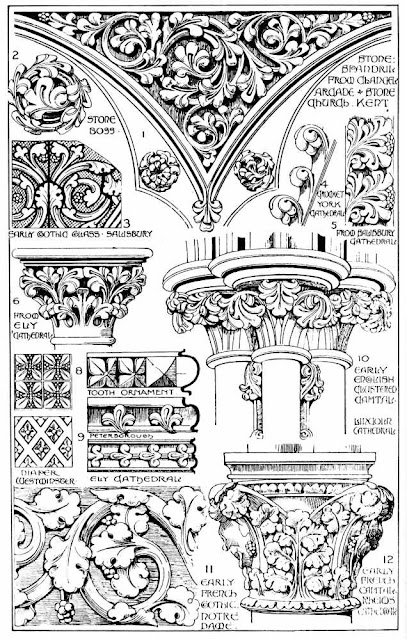

The Norman style was succeeded by the pointed, or Gothic style, remarkable for its variety, its beauty of proportion, and the singular grace and vigour of its ornament. Showing no traditions, beyond Sicilian and Arabian influence, it grew rapidly, and reached a high degree of perfection in France and England.

The massive and barbaric character of the Norman style gave place to the light clustered shafts and well-proportioned mouldings of the early English Gothic, with its capitals characterized by a circular abacus, and the typical three-lobed foliage growing upwards from the necking of the shafts, thence spreading out in beautiful curves and spirals under the abacus.

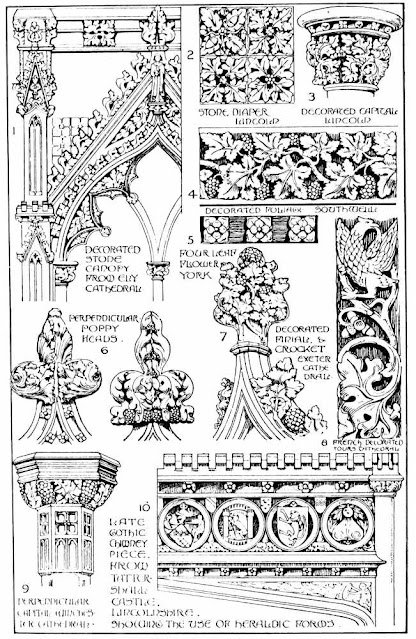

This tendency to the spiral line is peculiar to the early Gothic, and differentiates it from the Decorated and Perpendicular Period. The diagrams of the three crockets here given show the distinctive character of English Gothic ornament.

A. Early Gothic, three lobed leaves arranged in spiral lines.

B. Decorated Gothic, with natural types of foliage, such as the oak and maple, with a flowing indulating line.

C. Perpendicular Gothic, showing the vine and leaves as elements, and arranged in a square and angular manner. The same features and characteristics are observed in the borders here given.

The beautiful carved spandril from the stone church, Kent (fig. 1), is remarkable for the vigour and flexibility of curve, its recurring forms of ornamentation, and admirable spacing, typical of much of our early English foliage.

The type of foliage in early English stained glass is somewhat similar to contemporary carved work, but showing more of the profile of the leaf, and it has a geometric or radiating arrangement in addition to the spiral forms of foliage.

Early French work (figs. 7 and 8), with its square abacus, differs from the early English, in having less of the spiral arrangement, and a rounder type of leaf, together with the absence of the mid rib, which is so characteristic of contemporary early English Gothic. The plain moulded capitals so prevalent in this country are rarely found in France.

DECORATED AND PERPENDICULAR

GOTHIC DETAILS. Plate 17.

DECORATED & PERPENDICULAR GOTHIC DETAILS

Decorated Gothic is remarkable for its geometric tracery, its natural types of foliage, and the undulating character of line and form in its ornamental details. The foliage of the oak, the vine, the maple, the rose, and the ivy were introduced in much luxuriance and profusion, being carved with great delicacy and accuracy. Lacking the dignity and architectonic qualities of the early Gothic foliage, it surpassed it in brilliancy and inventiveness of detail. The Capitals, enriched with adaptations from nature, carved with admirable precision, were simply attached round the bell, giving variety and charm of modelling, but lacking that architectonic unity which was so characteristic of early work.

Diaper work, crockets and finials, introduced in the early English, were now treated with exceeding richness, and used in great profusion. The ball flower so characteristic of the Decorated period replaced the equally characteristic tooth enrichment of the preceding style.

French Contemporary Work has similar characteristics, but displays more reserve and affinity for architectural forms.

This brilliant Decorated period reached its culminating point within half a century and then rapidly gave place to the Perpendicular Style, with its distinctive vertical bar tracery of windows and surface paneling, and the prevalent use of the four centered arch—of octagonal capitals enriched with the angular treatment of the vine,—of heraldic shields and arms, and of the four-leaved flower; all typical of the period.